Five Black Pioneers You Should Know About

February 08, 2022

UMD faculty and staff share stories of overlooked figures From American history.

By Karen Shih ’09 | Maryland Today

While Martin Luther King Jr., Harriet Tubman and Rosa Parks step to the forefront of school curricula in February, many more Black pioneers have made critical contributions to U.S. history, from theater to journalism to education.

“In my studies, there have been many lesser-known figures whose names are starting to appear now, as people increase their focus on diversity and inclusion,” said Georgina Dodge, vice president for diversity and inclusion, who earned a doctorate in English. “There’s so much history I’m steeped in that hasn’t been of interest, but it’s gratifying to see it come to pass now.”

During this Black History Month, Maryland Today asked University of Maryland faculty and staff to share stories of Black trailblazers who they suggest should be more widely recognized today.

Theresa Harris, Actress

Next year, students in the School of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies will perform “By the Way, Meet Vera Stark,” at The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center under the direction of professors Scot Reese and Alvin Mayes. The play by Lynn Nottage, based loosely on the life of little-known actress Theresa Harris, tells the story of a young woman of color trying to break into the film industry in the 1930s while working as a maid to a fading starlet, said Reese.

“When you watch Harris alongside Barbara Stanwyck in the film ‘Baby Face,’ it’s Harris who lights up the screen. But her career was cut short because she was limited in who she could play. They darkened her skin, made her a maid, because it was more palatable for Americans to see her that way.

“The Hays Code in 1934 really changed the way Hollywood depicted Blacks on film. The commission [that created the code] said Blacks couldn’t have the same stature as whites. We could have had a completely different track for Blacks in theater, TV and film—but because of the code, we had to be lesser citizens.

“Though I’ve taught Black theater performance for years, it’s because of Lynn Nottage that I was introduced to Harris. Pulitzer Prize winner Lynn Nottage made history having a play, a musical and an opera all running at the same time in NYC!”

Samuel Cornish, Newspaper Editor

The fight for Black equality in the first half of the 1800s, when many Black Americans remained enslaved, required the leadership of people like newspaper editor Samuel Cornish, said Christopher Bonner, associate professor of history. He brought to light the efforts of Cornish and fellow activists in his 2019 book, “Remaking the Republic: Black Politics and the Creation of American Citizenship.”

“In March 1827, Samuel Cornish helped establish Freedom’s Journal, the first Black newspaper published in the United States. Born free in Delaware, Cornish had moved to New York to pursue his work as a minister. He eventually focused his energy on activism when he recognized the legal and economic inequalities of Black life in the North. Freedom’s Journal transformed African American protest, collecting and publicizing Black people’s arguments about inequality and organizing Black activist communities.

“Cornish would go on to lead two additional Black newspapers and engage in many of the critical forms of African American politics from this period. In their writing, Cornish and others spoke to white lawmakers and demanded equal justice in loud, public voices. At the same time, African Americans worked outside the law to support one another, helping fugitive slaves secure freedom in the North and organizing mutual aid efforts to alleviate the burdens of poverty. I find Cornish to be especially important because his work reflects some of the many ways Black people showed their care for one another. And learning about his activism offers valuable lessons regarding the ways people can pursue collective liberation from oppressive circumstances.”

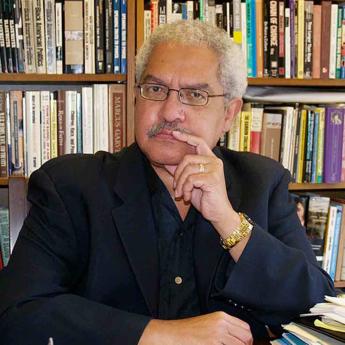

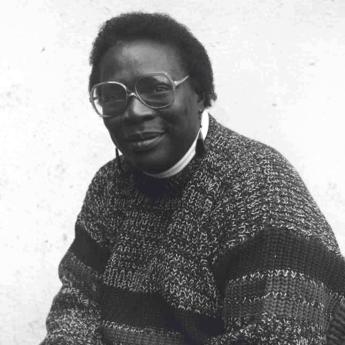

Manning Marable Ph.D. ’76, Scholar and Author

As part of the mission of TerrapinSTRONG, the new UMD onboarding program designed to create a more inclusive community by acknowledging the university’s multifaceted history, Program Manager Leslie Krafft is unearthing stories about UMD pioneers. One of those is the late Manning Marable Ph.D. ’76 (history), a professor of public affairs, political science and history at Columbia University and a lecturer for the Sing Sing Prison Inmates’ Master’s Degree Program. Inducted into the UMD Alumni Hall of Fame in 2005, he was posthumously awarded the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for History for his book, “Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention.”

“Marable's writings on African American history are some of the most-read scholarly works in the U.S. His Hall of Fame entry says his contributions include ‘defining the Black experience in America, from the slave trade era to a political election cycle. … He raised awareness of issues related to civil, prisoners’ and labor rights through his nationally syndicated column, “Along the Color Line,” first published in 1976.’ If you want to learn more about him, you can start with his biography for thehistorymakers.org, which includes video interviews with Marable.”

Pat Parker, Poet and Activist

Poetry can be a powerful tool to call out injustice, as Pat Parker showed through her prolific writing, said English Professor GerShun Avilez. He highlights her work in his 2020 book, “Black Queer Freedom,” and calls for greater recognition of her civil rights advocacy for a multitude of causes from the 1960s through 1980s.

“A trailblazing poet and activist, Pat Parker was active in Black, feminist and queer organizations. She was involved with the Black Panthers in the 1960s and a member of the Lesbian Tide Collective in the 1970s. She founded the Black Women’s Revolutionary Council in 1980. Accordingly, she is a key figure in the history of radicalism in the late 20th century. Parker published five books of poetry: “Child of Myself,” “Pit Stop,” “Movement in Black,” “Womanslaughter” and “Jonestown & Other Madness.” Her poems consistently critique racism and homophobia, but they also emphasize the value of pleasure. Throughout her work, Parker shows a commitment to feminism and Black history, especially in her trademark poem “Movement in Black,” an epic history of Black women. The motivation behind her art and activism can best be summarized by her assertion, “I’m waiting for the revolution that will let me take all my parts with me!”

“Parker has been an inspiration for my research, especially my recent book, “Black Queer Freedom.” In it, I analyze poems such as "Movement in Black" and "Where Will You Be?"—my personal favorite—and how they help us to understand Black and queer identity in the past and today.”

Read more in Maryland Today.

This is one of a series of Maryland Today features during Black History Month celebrating Terp faculty, staff, students and alums.

Photos by Wikimedia Commons; collage by Stephanie S. Cordle.